The accident that occurred during the first lap of the Bahrain Grand Prix involving French driver Romain Grosjean was horrifying, bringing back bad memories of the past where images of cars on fire was commonplace, but it’s something we’re not used to seeing in modern Formula 1.

The technological developments implemented over the past decade to improve safety have been vast and it’s these, plus a little bit of luck, that allowed Romain Grosjean to come out practically unharmed (or almost) from an accident that will be remembered for some time!

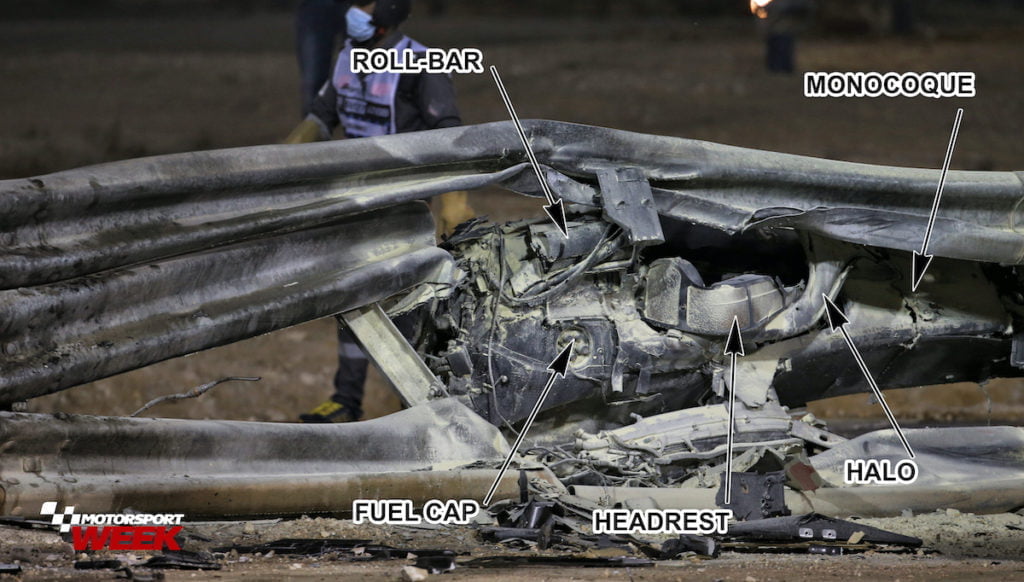

By thoroughly analysing the replays of the accident and the photos of the wreckage, it is possible to trace the reasons why the car literally broke into two sections, why the explosion that caused the fire occurred, and what allowed the driver to walk away.

DYNAMICS OF THE ACCIDENT

The accident occurred on the straight between Turns 3 and 4, with Grosjean turning to the right and making contact with Daniil Kvyat’s Alpha Tauri, triggering a semi-spin at over 250 km/h.

The Haas veered off track and into the guardrail on the right of the straight, with the barriers falling back towards the track at that point due to an escape path. The impact against the barriers occurred at an angle between 30 and 45° frontally, with a speed of about 180 km/h, and a deceleration of over 50G.

The guard rail, deforming itself, absorbed a large part of the kinetic energy released by the impact. However the post supporting the barriers acted as a pivot to the car, which rotated the rear axle clockwise, effectively breaking the Haas into two parts approximately in the centre. The rear part, containing the engine/gearbox remained on the track, while the front (the one containing the French driver) remained wedged inside the guardrail, opening it in the centre. A few seconds of fraction after the impact, a huge fireball was seen rising into the air, enveloping the scene of the accident.

WHAT CAUSED THE FIRE?

The fire that engulfed the Haas VF20 was caused by a fuel spill. It is not to be associated with a short circuit due to the electrical part or batteries. The energy store, in fact, as you can see from the photos, did not ignite the fire. The battery pack (energy store) is basically located under the driver’s seat, in the rear part, in a sort of niche formed by the frame, in which the whole package of control units and batteries is housed. The energy store remained anchored to the rear half of the car, in front of the Ferrari engine.

The leak of petrol, on the other hand, is not attributable to the puncture of the kevlar-lined fuel tank, which has remained intact. The tank contained within it a substantial amount of fuel given it was the first lap of the race. The weight of fuel that the Haas carried on board at the moment of impact was about 110kg, if this had ignited the explosion would have been far, far larger!

According to local insiders, and from some photos that emerged by analysing the wreckage of the chassis, the gasoline that caught fire escaped from the sheared fuel lines when the car split in two. These lines are self-sealing, like those of airliners, when there is a leak to avoid fires like this and it’s why they are so rare. However, the refuelling cap on the right side of the car was blown off in the impact because of the severity of the crash and the pressure exerted by the fuel (opinion of motorsport engineer Gabriele Tredozi in an interview). This was the cause of the fire.

WHAT HAS AFFECTED THE SAFETY OF THE CAR?

One of the fundamental things that saved Romain’s life were of course his own actions, as he was immediately able to unfasten his seat belts (easily unlocked by a button in the centre), and removed the headrest (cockpit paddle), allowing him to extricate himself and jump away from the burning car. The steering wheel, according to the driver’s statement, detached itself on impact, allowing for a quicker escape, not further prolonging the 28 seconds Grosjean spent engulfed in flames.

Thanks to the neck protectors (HANS system), the Halo, and the safety cell of the carbon-fibre chassis, Grosjean was able to remain conscious and lucid in order to carry out all the correct procedures to get out of the cockpit in less than 28 seconds.

The fact that the car broke in two, substantially in the weakest point of the structure (i.e. where the chassis engine mounts are), also helped to dissipate most of the kinetic energy, not discharging it all in a single block.

Of the wreckage of the front of the car, essentially the survival cell of the chassis remains, which is the part where the car’s cockpit is located. For years the FIA has made progress on safety, requiring teams to pass various crash tests, to protect drivers in the event of such an accident.

The cell remained intact, only the anti-intrusion cones on the side of the passenger compartment were blown off. Some cracks have been seen, and part of Zylon that covers the body (a polymer used as an anti-intrusion material in case of collisions) has slightly peeled away. However, everything held up well overall, and provided enough safety for Grosjean to live to tell the tale.

The most fundamental safety feature of all was the FCP (front cockpit protection) system, commonly called the halo, which essentially split the guardrail plates, ensuring they didn’t come into contact with the driver’s helmet. There have been many criticisms of this system, in the opinion of many unsightly, but which was vital more than anything else to protect the driver’s head. It was also vital in accidents that occurred in the past (for example in Spa 2018, in the Alonso-Leclerc accident). The Halo system, introduced in 2018, is an element composed mainly of titanium alloy, and covered in carbon leather. It is approved to withstand very violent impacts, with applied forces of up to several tons. The drawing below shows up to how many kilo newtons the FCP system can resist.

Finally, the work done by the fireproof race suit was also very important, as well as the various fireproof clothing that the pilot must wear in each session. All F1 cars are approved to withstand almost 1 minute inside the flames, protecting the driver’s skin from injuries and burns due to heat. The suits are made of four layers of Nomex, a polymer capable of resisting fires. These suits go through a rigorous process of washing, drying and testing at temperatures between 600 and 800 degrees. All the details, from the zip to the gloves to the socks must withstand the same temperatures. To further reduce the weight, the sponsor logos are no longer sewn patches, but are printed directly on the suit.

WAS THERE ALSO GOOD LUCK?

Surely luck meant that we did not find ourselves telling a tragedy, but simply reminded us that “motorsport is dangerous”. The fact that the accident occurred on the first lap allowed the Medical Car to quickly reach the crash site. The FIA protocol provides that the Medical Car follows the cars on the first lap, in order to intervene quickly in the event of an accident. The crew intervened to quickly rescue Romain from the flames, and to help the marshals (quite inexperienced in using the fire extinguisher) to tame the flames.

The same marshals, as in Imola, found themselves crossing the track after the engine failure that occurred on Sergio Perez’s car while Lando Norris was passing, who promptly avoided the obstacles. In this regard, an investigation will be opened by the FIA, to better investigate the dynamics of the accident.

The race director himself, Michael Masi, went to the scene of the accident, while the experts were fixing the torn guardrail. To understand if it will be appropriate (by now for next year) to change the position of the barriers, which at that point dangerously converge towards the track, at an angle of about 15°.