John Horsman, the British engineer who passed away Monday aged 85, was tremendously influential in the endurance racing world.

How influential? He made the Porsche 917 into the legend it is today.

While affiliated with John Wyer and his JWA Gulf operation, the Briton worked to develop some of the most iconic racing cars of all time. He took the blue and orange Ford GT40s to two straight wins at Le Mans in 1968 and 1969, doubling his already existing tally from his stint with Ford’s factory operation.

His work on the now legendary GT40 simply can’t be denied, but it wasn’t until JWA became the official Porsche works squad when Horsman met his most famous match: the Porsche 917.

Of course, it should be noted that John Horsman did not create the 917. The mid-engined monster, based on the pre-existing 908, was the brainchild of the late Ferdinand Piëch and designed by chief engineer Hans Mezger. The 917 arrived in 1969, when Horsman and Wyer were still hitting it big with the GT40. But while the Oldham native wasn’t the 917’s inventor, he was undeniably fundamental in shaping it into the legend we know today.

A deadly first act

Most people know 917 as a winning machine. The iconic Steve McQueen-mobile, unstoppable from the word go. But that’s not the full truth.

When the 917 first arrived, it sure was fast, but it had some horrific handling issues. It was so bad that Porsche’s stars of the day sometimes simply refused to drive it, reverting back to the old 908, particularly on twisty circuits like the Nürburgring Nordschleife.

The problem, as was later discovered, was that the car was simply too fast for its own body. The original 917 was designed with a low-drag, long tail body. This became an issue as the 917, powered by a 4.5 liter flat 12 engine, was significantly quicker than any race car that had previously come out of Weissach. The car had been set up as a low-drag machine, like previous slower Porsches, but as a result the car’s rear end had a serious lift problem at high speed.

The problems even proved fatal. Gentleman driver John Woolf perished on the opening lap of the 1969 24 Hours of Le Mans after crashing his 917.

The eureka moment

This was all solved during a late 1969 test in Austria. JWA Gulf had been contracted by Porsche to become the official factory outfit and were testing the car at Zeltweg when Horsman came up with the stroke of genius that would solve the 917’s achilles heel. While testing, the air at the track was heavy with flying insects, which caused Horsman to notice something. As he explained in his book Racing in the Rain:

“I noted there were hardly any dead gnats on the rear spoilers. Since they are very small and light, I knew the gnats would flow over the bodywork exactly as the air flowed, and similar to the smoke from wands used in wind tunnels.

“I knew immediately that we had to raise the rear deck and then attach small adjustable spoilers to the trailing edge. It was obvious to me that if the whole rear body surface was in the airstream, it would be able to exert some downforce.”

With a slap-dash, do-it-yourself solution fashioned out of bits of aluminium and armco barrier, Horsman and the JWA Gulf crew created temporary new bodywork for the troubled car. As rudimentary as the solution was, it proved vital. The makeshift body transformed the car and laid the groundwork for a remodeled version. From that, the 917K was born, with the K short for Kurzheck, which was the German word for short tail.

The 917K proved a behemoth of a racing car. It debuted at the 1970 24 Hours of Daytona, where JWA entered two cars. The team took a one-two finish in a display that was nothing short of utter dominance. The #2 car, driven by the trio of Pedro Rodriguez, Leo Kinnunen and Brian Redman, beat the sister car to the flag by a staggering 45 laps.

Le Mans – Glory at the race and on the big screen

The Porsche 917K would go on to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans twice in a row. First in 1970, giving Porsche its first ever overall win, and again in 1971. Ironically, while Horsman saw ‘his’ car win the French endurance classic twice, it never crossed the line first in blue and orange. The 1970 victory was taken by Hans Herrmann and Richard Attwood for the Austrian-based Salzburg crew, while Gijs van Lennep and Helmut Marko took the Martini International machine to glory in 1971.

While JWA Gulf would never win the great race with the 917K, the car was etched into the world’s consience as part of the 1971 film Le Mans, in which Steve McQueen’s Michael Delaney races a blue-and-orange 917K. The movie was famously filmed at the 1970 edition of the race.

McQueen was an avid racer himself and actually took a class win for with Porsche at the 12 Hours of Sebring earlier in the year. The actor was even originally supposed to enter the race alongside none other than Jackie Stewart, but his entry ultimately fell through. To this day, rumours still persist that he actually drove a stint on Sunday morning, although this tale has never been fully substantiated.

Championship dominance

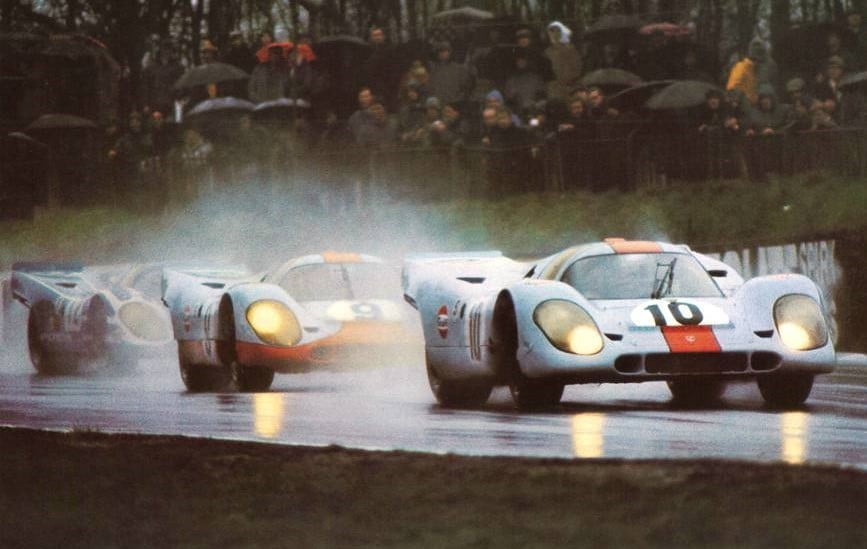

Outside of Le Mans, the 917K was a dominant car for both the 1970 and 1971 World Sportscar Championship. Ferrari had stepped up to the challenge with its new 512, but was unable to hold a candle to the force of nature that was the 917K. John Wyer Automotive won seven out of ten rounds in 917, only losing out to the Salzburg team at the Nürburgring and Le Mans and to Ferrari in Sebring. Pedro Rodriguez’ now legendary dominant display in torrential conditions at Brands Hatch was one of four wins the Mexican and Leo Kinnunen took en route to the title for Porsche.

Sometimes referred to as “the day they forgot to tell Pedro it was raining”, Rodriguez put in the drive of his life behind the wheel of #10 car to recover from a penalty that had dropped him to twelfth overall, only to fight back, take the lead within half an hour of the race start and lead a Porsche 1-2-3-4, finishing five laps ahead Vic Elford and Denny Hulme in second place. The Mexican spent 5,5 of the nearly seven hours behind the wheel of his car.

Porsche won the title again in 1971, fending off more fierce competition from Roger Penske’s privateer Ferrari effort as well as the Alfa Romeo T33/3 that took three wins at Brands Hatch, the Targa Florio and the final round at Watkins Glen.

The season included the second Le Mans win for Porsche courtesy of Van Lennep and Marko. JWA finished second, with Richard Attwood and Herbert Müller two laps down on the winners, but nearly thirty laps clear of the nearest Ferrari challenger.

After the 1971 season, the car was outlawed. Porsche turned its attention towards racing in America, while Horsman gave JWA Gulf a final overall win in 1975 when he managed the Mirage programme. Gulf closed the book on its racing programme at the end of that season.

An iconic legacy

John Horsman’s contributions to endurance racing’s are hard to overstate. He was involved with Le Mans-winning machinery across several decades, but it is that single stroke of genius on an autumn day in Austria in 1969 that is perhaps a crowning achievement.

With his legendary attention to detail, Horsman was able to turn a ill-handling, dangerous car into a Le Mans winner and a car that has become an icon in motorsport history that endures even today.

Discussion about this post